Sunday, August 19, 2012

There Is A Bitten Thing.

Do Not Put The Finger.

Sheila requests a minute outside the blindfold.

Sheila requests a minute, but Sylvia tells her no, tells her to return to a kneeling position, reminds her that this is the arrangement they agreed upon and this is the arrangement that will remain until the time ~ almost two more hours, according to the big digital clock on the warehouse's north wall, the glowing numbers shifting in relentless, calibrated procession, searing crimson against their rectangle of electric black ~ until the time they agreed upon for the arrangement to end.

Picture blindfolded Sheila: Kneeling, naked; a long narrow scar on her left shin from a childhood fall from that year's Christmas bicycle; not overly fond of cauliflower as a rule but glad to indulge if it's part of a diverse stir fry that also includes a bit of shredded ginger; most relaxed when it's just her and her old cat on the balcony of her third-floor condo at twilight in the cooler part of the summer and the entire discography of the Quintet of the Hot Club of France on shuffle on her iPod; ignorant of all but the first two chapters of Ingeborg de Gruyter's erotico-scientific handbook Cleavage to Beaver.

(Sylvia, though, has read that handbook so many times, cover to cover, that she's almost got it memorized.)

"Bend forward a little more," says Sylvia.

Sheila does as she's told, her back curving, her abdominal muscles tightening. She places her hands on her knees to add support.

"That's good," says Sylvia. "That's perfect." She scoots forward in the wheeled office chair, rolls farther across the concrete floor until she's directly behind Sheila, the front of the chair's upholstered seat almost touching the small of Sheila's back.

"Okay," says Sylvia. "This has been in the refrigerator ~ it might be a little cold." She dips a long thin paintbrush into the ceramic bowl in her lap, gathers a bit of natural henna paste onto the brush's bristles.

Sheila shivers as the brush touches her skin for the first time, but remains silent as Sylvia inscribes words upon her back. Sylvia paints the words in elegant cursive, working henna into the pale skin, painting from left to right between Sheila's slight shoulders, one sentence all the way across, and then ~ after a pause in which Sylvia runs the fingers of her left hand down the side of Sheila's neck, shifting the long dark tangles of hair that hang there, giving the henna time to fully bind to Sheila's epidermal proteins ~ another sentence below.

You might have driven past this warehouse one day. It's there on the Eastside of Austin, not too far from where Industry Screenprinting used to be, close to the metalworks collective where Sixth Street ends, a few minutes' walk from the Salvadoran delicacies of El Azunzal, over where the letters of the familiar grocery store might better stand for Hispanic Enormous Bodega.

Sylvia and Sheila are borrowing the warehouse for this day only, for this purpose specifically, and it isn't costing them a thing. Sylvia has many friends, connections, a strong line of credit in the local favor bank. Sylvia is, if anything, resourceful.

"Now lean back a little," says Sylvia. "That's it, straighten your body. That's good. Hands at your sides."

Sheila obeys, kneeling there atop a black silk cushion on the warehouse floor.

Sylvia kneels in front of Sheila, facing her. Sylvia is also on a cushion, but she's fully clothed: Loose white T-shirt; the powder-blue of old Levis more tightly fitted around her hips and ass and legs, almost snug in the crotch; a pair of black Converse that her last girlfriend bought for her in Houston five years ago. She's got a small wooden tray next to her, filled with papers, the papers weighed down by something long and thin that projects several inches beyond the tray's short walls and is wrapped in a swath of the same black silk that Sylvia used to make the cushions upon which she and Sheila kneel. She digs into the right front pocket of her jeans, pulls out a clear vial filled with viscous liquid.

"Okay," says Sylvia. "This hasn't been in the refrigerator."

A smile flickers across Sheila's lips. "Is this ..."

"The clove oil," says Sylvia, unscrewing the vial's cap and trapping it easily in the curl of her little finger. She pours the oil into the palm of her left hand, forming a little pool of it there. She sets the emptied vial on the floor, screws the cap back on, returns the vial to her pocket, all the while making sure that her left hand remains level, that the oil doesn't spill out.

Sylvia puts her right hand over the liquid-filled left and rubs them together until both palms are slick, are almost dripping with the pungent oil of cloves.

"It smells like a dentist's office," says Sheila.

"Shhhhhh," says Sylvia. She leans forward and kisses Sheila on the lips, as if to seal them from further speech, then reaches out and places her right palm between Sheila's small breasts. "This might get kind of warm," she says.

Sylvia moves both her hands against Sheila's chest, spreading the oil across skin, over areolae and nipples.

Sheila's jaw clenches.

"Is it burning you, love?" asks Sylvia.

"Not really burning," says Sheila tightly. "It's just ~ yeah, it's getting pretty hot. Especially on my nipples."

"It'll pass," Sylvia assures her. "Just give it a minute, it'll fade."

Sheila breathes deeply to calm herself, her mouth partly open, her glistening chest expanding and contracting as she kneels, naked and blindfolded in front of Sylvia, upon a small silk cushion near the center of a refurbished warehouse on the Eastside of Austin, Texas.

Numbers shift, marking time's advance on the big digital clock. There's a stuttered rumbling of some large truck passing by outside.

"Ah," says Sheila, finally relaxing. "That's better."

"Good," says Sylvia, wiping her hands on the bottoms of her jeans' legs. She pulls the wooden tray closer, takes the silk-wrapped object from atop the papers and sets it to one side. "Okay," she says. "These are the pictures I told you about. I'm going to transfer the images to your chest, one at a time, and I won't stop until they're all done. You … you just stay quiet, understand?"

"Yes, my love," says Sheila.

Sylvia picks up the first picture. It's the photo-reproduction of a face, screenprinted in jellied blackberry juice onto a sheet of onionskin paper. (The other sheets, also onionskin, are printed with other faces ~ originally from paintings or photographs ~ in the same manner. There are, including the one Sylvia's holding, thirteen such sheets.) Sylvia places the sheet of printed onionskin against Sheila's chest. She smooths the delicate paper with the palms of her hands, flattening Sheila's breasts, working the blackberry image into the clove oil, onto skin.

"Sappho," says Sylvia, naming the image upon Sheila's chest. She peels away the sheet and sets it behind her. The paper is translucent with clove oil; the image remains, faintly, on both onionskin and Sheilaskin.

Sylvia picks up the next sheet and repeats the process; then again, then again, twelve more times in all, speaking each image's name as Sheila's chest becomes a palimpsest of indecipherable violet lines and shapes, as the sheets of saturated onionskin pile up behind her.

"Geoffrey Chaucer," says Sylvia. "Aleister Crowley. Ada Lovelace. Shirley Jackson. Richard Feynman. David Lynch. Joss Whedon. Hedy Lamarr. Pamela Zoline. Aimee Weber. Tony Millionaire. Kathy Acker."

You might have one of those small wooden trays of your own. Their proper name, according to the Container Store's extensive catalog, is: Modular Bamboo Drawer Organizer. The Modular Bamboo Drawer Organizer next to Sylvia's right knee is the 6" by 6" model ~ $6.99, crafted from solid bamboo, with "a warm, natural finish that looks great inside a drawer or on top of a counter, shelf, bureau, or desk" ~ that she bought from the store on Research Boulevard, where, coincidentally, Sheila had worked as an assistant manager until a year before Sylvia moved to Austin.

The process is complete.

Sheila breathes, a complexly marked bellows.

Sylvia picks up the thin, silk-wrapped object.

She uncovers it.

It could be the end of an ancient spear, something from the Stone Age, its point blunted by much use and centuries of weathering. There are thirteen inches of it, nearly as pale as Sheila's skin and polished to a dull shine, its smoothness textured by helical striations.

Sylvia places its cool length against the inside of Sheila's left thigh.

"Oh my god," says Sheila. "Is that really ... ?"

"Yes," says Sylvia. "It really is."

"Oh my god," says Sheila again, hands gripping her hips in excitement.

"The most conspicuous characteristic of the male narwhal," Wikipedia reports, "is its single 7-10 feet long tusk. It is an incisor tooth that projects from the left side of the upper jaw ans forms a left-handed helix. The tusk can be up to 9.8 feet long (compared with a body length of 13-16 feet) and weigh up to 22 pounds."

Of course, narwhal tusks ~ even the broken-off tip of one, like what's being held against Sheila's thigh ~ aren't easy to acquire. But Sheila knows Scott Webel of Austin's Museum of Natural and Artificial Ephemerata, and Webel has a friend who has a friend who works at the Boston Marine Society, the "oldest association of sea captains in the world;" and Webel's friend's friend has long wanted to spend a weekend exploring Fredericksburg, just an hour outside of Austin and where that friend's forebears had first immigrated to; and Sylvia, due to an article she wrote for Travel magazine years ago, has long had an open invitation to spend a few days at one of Fredericksburg's better bed & breakfast establishments. And Sylvia is, if anything, resourceful.

"I hold in my hand the tusk of a narwhal," says Sylvia, her voice almost singsong, as if chanting to invoke some eldritch power. "The foremost part of the legendary narwhal's tusk is what I hold, my text-ridden, image-stained love." She slides the polished rod farther, until its smooth blunt tip is tickling Sheila's pubic curls. "And what," says Sylvia, "do you think I'm going to do with it?"

Tuesday, June 12, 2012

Gnap! Theatre Projects'

SHANNON McCORMICK

Is In Dutch But Good

PHOTO BY KENNETH GALL

Back in the day ~ and I mean back in the day, when tall ships ruled the seas and human flight was centuries away; back when the British were dissing Netherlanders so constantly that a small squadron of adjectival phrases barnacled itself onto the shifting hull of everyday speech ~ being “in Dutch” meant being in disfavor with someone.

That meaning still obtains, although, these days, the term is mostly vestigial. It’s used in the title above to suggest an answer to the riddle: When is Shannon McCormick not Shannon McCormick?

Because that McCormick ~ the founder & artistic director of Gnap! Theatre Projects, the male half of Austin improv duo Get Up, a former producer of the Out of Bounds Comedy Festival, a former member of Backpack Picnic, a frequent voice actor for all manner of animated endeavors, and so on, and so on ~ that McCormick’s got sort of an alter ego who goes by the name of Cornelius de Vries.

Now, Cornelius is not a relentless identity ~ like Sybil or something. Cornelius is a definite staged show: An ongoing series of one-man improvised monologues, in which McCormick relates the various experiences of a Dutch merchant who lived from the years 1600 to 1700.

I know, right? It sounds a bit … drier than the typical entertainments found in the often-wacky world of improv. And this anomaly is why it’s initially intriguing, but there are two reasons why the concept continues to fascinate: 1) The character’s life is fascinating, and 2) McCormick’s skill in bringing that life to vivid expression is nonpareil. The show even succeeds among general audiences looking for their usual idea of comedy improv, because, although the performances are never worked specifically for laughs, Cornelius himself can be quite witty.

So I’m focusing on Cornelius not just because that was a good excuse for the title’s pun, no. (I mean, hey, heaven forfend.) But neither am I showcasing the character only because the character is so intellectually fascinating. After all, McCormick himself, like most ~ hell, like maybe all ~ of the people featured in this ongoing Wreck, is sufficiently Of Interest without having to spotlight some fictional herring-chomper of a geezer he portrays in various venues across town.

No, the Cornelius focus was sparked by its visual potential. Due to the excellence of full-color print technology. Due to the sartorial gambits afforded by a 17th-century spice merchant. Due to the professional skills and generosity of photographer Jon Bolden.

I mean, just look at this finely draped peacock:

PHOTO BY JON BOLDEN

So let’s never mind McCormick’s original one-man show, Unbeaten, for which he collaborated with composer Graham Reynolds and videographer Lowell Bartholomee to create and perform a live, multicharacter narrative about two brothers battling each other on opposing pro football teams. Never mind him providing the voices of Akabane Kuroudo for the Getbackers anime and The Riddler in that new DC Universe MMORPG. Never mind his years wrangling the annual operational juggernaut that is the Out of Bounds Comedy Festival. And never mind the college-era writing awards, the sojourn in Prague, the stint as Mysterion in The Intergalactic Nemesis, the year and a half as program manager at Salvage Vanguard Theater, the wife and two kids and gray-muzzled Rhodesian Ridgeback, the daunting knowledge of pop and esoteric culture.

Never mind any of that personal and creative bounty. Except as background shading, as what underlies only the first of the two pages of interview that follow and end with a brief conversation with the resplendent Mr. de Vries …

Brenner: The Out of Bounds Comedy Festival ~ you didn’t start that, and you’re not producing it now. But you did for a while, right?

McCormick: I produced it for five years. And in a lot of ways, I think they were the formative five years. It was run for two years by Jeremy Lamb, who started it, and the Well Hung Jury. And I don’t think there was anybody playing who was from outside of Texas those first two years. Maaaaaybe one or two people. And then, in 2004, Mike D’Alonzo and I took over the production of it, and we concentrated on getting people from out of town to apply. We expanded the range and established the reputation of Out of Bounds as a great place to come and play.

Brenner: And besides making it a national thing, weren’t you and D’Alonzo also the guys who moved the festival into formats beyond improv?

McCormick: I think that probably would’ve happened regardless of who was doing it. I don’t even remember when we first started including sketch. There may have been sketch in 2002, 2003, and a lot of that had to do with who we knew.

Brenner: Like the Edmond Bulldogs and the Latino Comedy Project?

McCormick: Exactly. I mean, frankly, there wasn’t enough improv in Austin back in the day to fill up even a three-day festival.

Brenner: Which seems really weird now.

McCormick: Totally. It’s completely different.

Brenner: And what does producing mean, at least as far as the OOB is concerned?

McCormick: It’s about making sure that all of the aspects of the shows, besides the art itself, come off well. So: marketing, website maintenance, ticket sales, making sure that all the performers coming in from out of town have accommodations of one kind or another and are taken care of, made to feel welcome. It’s a huge time commitment ~ it’s definitely a labor of love. And when I had my second child, I decided that it was just too much effort for what I was gonna be able to give it. And Jeremy came back on as a producer, and now he’s the sole executive producer of the festival.

Brenner: How was running the OOB different than being artistic director of Gnap! Theater?

McCormick: Well, that’s the other thing: I wanted to concentrate on producing my own work. And, producing Out of Bounds, it’s a lot of time and effort to showcase other people and their talents and putting them forward. And that’s fine, there’s a place for that, and I think it’s a noble thing to do. But since I had to make a choice, I wanted to be in a spot where I was concentrating more on producing my work and the work that I wanted to see come into the world independent of anybody else’s artistic notions.

Brenner: And what sort of things do you do, day-to-day producing Gnap!?

McCormick: My main responsibilities are programming the shows, figuring out what it is that we’re gonna do. Not necessarily directing them ~ in fact, I direct very few of them ~ but making sure that the shows that we do produce have a certain feel, that they fit in with our outlook, and creating the space for people to make their shows.

Brenner: What is that outlook? Where does the name Gnap! come from?

McCormick: It’s a terrible name for a theatre company. Nobody can remember it, they always mispronounce it. It started when I was an undergrad, and ~ no, let’s take this all the way back to when I was a little kid.

So there was an episode of The Smurfs called “The Purple Smurfs,” which is based on one of the actual Smurf comics from the 60s, by Peyo, called “The Black Smurfs.” But when Hanna-Barbera adapted it for the US market in the early ’80s, they felt that having the bad Smurfs be black was maybe not a PC way to go. So in the episode, some kind of butterfly bites one of the Smurfs on the tail and it renders the Smurf very angry, very aggressive and purple and highly contagious. So what the purple Smurfs do, they jump around and bite other Smurfs on the ass while shouting “Gnap! Gnap! Gnap!” That’s their vocabulary ~ it’s reduced to shouting “Gnap!” And it spreads like wildfire.

I can’t even remember how they solve the plague, but it is a plague. I mean, this insane Ionesco-like plague is visited upon the Smurfs. I think Smurfette, as a female, was immune to the thing, so it’s also, since it’s the early ’80s, it’s also this weird AIDS kind of metaphor, even though it wasn’t. But I found it to be one of the most trippy, subversive pieces of pop culture that I came into contact with as a kid, and it’s really disturbing. Those purple Smurfs, I mean, they’re really angry.

And so I was in college and, as you are wont to do in your early 20s, you obsess over and talk a lot about the pop-culture icons from your youth? And I used to talk about that episode all the time, about what a strange thing it was. And I had a group of friends who used to go to readings at the University of Iowa all the time ~ there were always a lot of awesome readers that would come because of the writing workshop there. And I don’t remember which writer it was, but it may have been J.M. Coetzee, the South African Nobel Prize Laureate? And he gave one of the most boring readings I’ve been to in my entire life. We joked that if you played his reading backwards, it would be him saying “I also won the Booker Prize.”

J.M. COETZEE

PHOTO BY MARIUSZ KUBIK

PHOTO BY MARIUSZ KUBIK

So it may have been that reading, or it may have been another one, where the author’s books were published by Knopf. So it was, “Blah-blah-blah from Knopf Publishing.” And my friend leaned over to me and whispered “Gnap! Publishing,” because of the similarly strange, pronounced letter at the beginning of it. And I found it really hilarious. And it stuck with me, and I thought, “That should be the name of something.” And so, when I started producing No Shame Theatre at the Hideout back in 2001, I decided that would be the name of the company.

And “stuck” is maybe not the right word: I have clung to it.

I should also say, though, that there’s something about it that speaks to the aesthetic I’m interested in. Which is: Having things be simultaneously really weird or subversive or just nuts, with things that are wrapped in this umbrella of popularity or just some kind of pop veneer. And which gets more emphasis, I’m not sure, but there’s something really powerful about that, that I’m really interested in. And also as a metaphor for theatre, I’m most interested in that kind of work that’s maybe a little bit infectious, that gets spread by word of mouth, the way the Gnap! disease gets spread. I think any artist’s ideal is to have that level of you’ve-gotta-know-about-this surrounding their work.

Brenner: Okay, here’s what must be a perennial question: You’re married, you have two young kids, you have a day job, and besides being a frequent performer and producer you’re also a relentless and rather deep consumer of more types of culture and creativity than I can keep track of, so ~ where the fuck do you find the time?

McCormick: I drink a lot of coffee. And it probably comes at the expense of other things. I am involved in a lot of things, and I’m maybe not as efficient in any one of those as I might be, were I not as busy in all the others. Gnap! would be better run if I didn’t also spend so much time reading or pursuing obscure comics on the Web as I do. And my marriage might be better if I didn’t also run a theatre company. All these things are wrapped up around each other. [shrugs] I’m just doing what I can, man.

Brenner: Where did your Cornelius character come from?

McCormick: It was a show in search of an idea, actually. ColdTowne Theater opened their venue back in the fall of 2006, right? And they were programming it, and Get Up ~ Shana [Merlin] and I ~ were sort of the first people to open up the improv community to the ColdTowne guys. We met them and rehearsed with them back when they first moved here, and I think they felt, “Oh, we should ask Get Up to play at our theatre.” So we booked a series of shows in December of 2006, and then Shana realized she wasn’t gonna be in town for most of the dates. So I needed to come up with a solo show. And there’s a pretty famous performer in the improv world, named Susan Messing, and her show is called “Messing With A Friend,” where she invites another performer to play and they do a two-person show. So I was thinking, “What can I do with my name that would be a sort of clever pun and also set up a solo improv format?” So I was thinking of famous instances of McCormick, and of course there’s McCormick Spices, which is probably the most famous one. And I was like, “Hey, I know a lot about 17th century Dutch culture! I’ll do an improv show where I’m this old guy who’s lived through an entire century and can just tell stories about it, as a spice trader.”

Brenner: You just ... happen to know so much about 17th century Dutch culture?

McCormick: When I was an undergrad, I was an art history minor, and I’ve always had a real affinity for Dutch art of that period. And when you learn about the art of that time, you end up learning a lot about the history of the Dutch republic as well.

Brenner: Ah. And is Cornelius ready to be interviewed right now?

McCormick: Sure. Of course.

[Except now it’s not precisely McCormick speaking: There’s a Dutch accent shading his speech ~ “Shoo-uh,” he says, “Uf caws.” His shoulders are slightly hunched, his head is drooping, his expressive hands suggesting the faintest tremor ~ as befits a geezer, regardless how physically fit, of circa 100 years. The slightly bemused look blooming on the man’s pale face is not one of McCormick regarding his friend Brenner but of Herr de Vries preparing to be questioned by some foreign journalist less than half his age.]

Brenner: Would you state for the record, sir, your name?

de Vries: Cornelius Corneliuszoon de Vries.

Brenner: Corneliuszoon?

de Vries: Corneliuszoon means “son of Cornelius.” That is the middle name of the Dutch, typically the father’s name, and so I am Cornelius, son of Cornelius.

Brenner: Kind of like Cornelius, Jr.

de Vries: Something like this.

Brenner: And what time are you speaking from? I mean, do you exist in our present, or …?

de Vries: The time is ~ what is the day, today? ~ April the ninth. Of 1700. I have recently celebrated my 100th birthday and have a century of knowledge of the past.

Brenner: How do you account for having lived so long ~ especially from the 1600s, when life expectancy was much lower than it is now?

de Vries: It is good hygiene. Also, ah, addiction to swimming in seawater, which is good for health of all kinds. And a daily glass of port ~ only one. And also, of course, the use of spices: pepper and other things that make life worth living.

Brenner: What’s your relationship with the Dutch East India Company?

de Vries: [smiles] Ah, you have asked a complicated question. But I have at times worked for them, including, at one point, having risen to the position of governor of some plantations in the Jakarta area, where there are many plantations of pepper and mace and nutmeg and things of this sort. I have worked at the, how would you say, corporate headquarters in Amsterdam ~ the V.O.C.’s main offices, where they dispatch many of the ships and keep the records of their trading. At other times I have been against them, as an independent raider of goods and services.

Brenner: You mean ... like a pirate?

de Vries: Like a privateer or pirate, yes ~ on my own ship or the ships of others. So we are a very strange relationship. We are, ah, twined ~ like the ropes on a ship. They are made of many strands, sometimes one is on top and the other is on the bottom: This is how I am related to the V.O.C.

Brenner: Did you have any involvement in the Tulip Mania?

de Vries: I was a young man, and I was abroad at the height of the tulip frenzy. But, also, my recommendation is for all who speculate in goods of all kinds, to buy early and sell early as well ~ because that is where the profits are. And I did trade a bulb of an Augustin’s tulip, for approximately 500 guilder at the time, then parted before the crash came. So I did very well with the tulip mania, unlike some of my countrymen ~ who were crazed by the flowers.

Brenner: What events in your childhood helped to make you the man you are today?

de Vries: I believe probably the most important was being, how do you say, taken to serve on ship against my will, as a young man.

Brenner: What we would call Shanghai’d.

de Vries: Yes. And this led to life on the sea. As a child at home, I was apprenticed to a tailor and would have spent my life sewing the clothes of aldermen and other wealthy individuals. Now I buy the clothes made by tailors.

Brenner: Were you reunited with your family, after you came back from the sea?

de Vries: Many of them.

Brenner: Many of them?

de Vries: I should say, I have had many families ~ in all parts of the world ~ and some are no more, and some know of me, and some, ah, want no knowledge of me.

Brenner: So you’ve reached your 100th birthday here. And what’s it been like, watching so many people that you’ve cared for ... watching so many of them die as the years have piled up?

de Vries: It is quite tragic, of course, to see this happen. But death comes for all, and we should not mourn the cycle of life that takes us away. Sometimes I wish that I had gone earlier than I have, for these reasons. It is also, em, quite painful to be so old.

Brenner: Cornelius, you’ve been all over the world, living the sort life most men can only dream of. With all of that behind you now, how do you pass the time of day?

de Vries: Drinking. And, also, with the telling of tales. Now that I am too old for new adventures, I stay young by reliving my youth, and a new energy comes over me.

Tuesday, April 10, 2012

LANCE 'FEVER' MYERS

is a highly animated fellow:

LANCE 'FEVER' MYERS

Lance Myers is currently working on a 20-minute animated video called The Boxer, featuring his character Twomey Martin, a pugilist with a secret. Myers has done plenty of big-studio work, too – A Scanner Darkly, anyone? Space Jam? Prince of Egypt? – even while crafting personal (and award-winning) projects The Astronomer (2000), Subsidized Fate (2003), and a comedy series called The Ted Zone for now-defunct SuperDeluxe.

We knew Myers first from Twomey’s appearance in Jeanette Moreno’s Moko comics anthology back in 1992, and were recently able to cajole the artist into creating an autobiographical comic for the final print edition of Minerva's Wreck.

(Eventually, Myers willing and the pixelcreek don't rise, we'll have those four pages up in here for your delight, too.)

Right now, we've got an interview with the man, conducted last year outside Tamale House on Airport Boulevard, both of us happily munching just, oh, perfect tacos at a storefront-shaded table beneath the big Texas sky …

SCENE FROM 'THE BOXER'

“The Boxer is sort of a snapshot of where I am, emotionally, about my work,” says Myers. “I’m doing everything myself, and I’ve had some very competent animators offer me their time to work on it – but I’m just not at the point where I can hand it off. I think I’ve come to terms with the fact that I’m gonna work a day job – and it’s a great day job – but it’s not entirely creatively satisfying. So I’ll have my side project that I hold dear to my heart, and it will be all mine. I want to be able to just, if I spend a year designing a character and creating all the animation, and then I look at it and decide it’s not quite what I had in mind, I can redo it. And I don’t have to explain that to anybody, I don’t have to justify it, I don’t have to re-plan my schedule. And it’s not gonna sell, and it may show in festivals – I’d love for it to show in festivals – but I’m not creating it to sell, I’m not creating it for anybody else. This is what I want to do, so I’m gonna do it.

"I’m lucky enough that I have a job and a life that allows me that," says Myers, "so I’m gonna take advantage of that and just make something I want to make.”

Brenner: Where are you working, these days?

Myers: BioWare. I’m working on that new Star Wars MMO that’s going to come out soon. Star Wars: The Old Republic. It’s gonna be enormous.

Brenner: So you’re doing The Boxer, which is your biggest thing so far, and like so many of your other projects, this one is animated. What is it that, uh, draws you to animation so much?

Myers: It moves. [laughs] Y’know, I went through various career aspirations as an artist. I wanted to be a cartoonist, and that’s why I moved to Austin in the first place. I was looking at the Daily Texan stuff, Jeanette [Moreno]’s stuff, and Tom King, and Walt [Holcombe]. Chris Ware and Korey Coleman and Karl Greenblatt. All those people who were doing that stuff in the early ’90s, at the Texan. And I wanted to be a part of it, so I moved here for that.

And then almost all of those people got interested in animation at the same time, and we all started working at Heart of Texas together. And of course there was the band thing. But as far as visual arts go, I went back to school and wanted to be a painter. And discovered that any time I did a painting, any time I did a static image, I was always trying to tell a story with it ~ and painting wasn’t the right medium for it. Some people can pull it off, like Robert Williams, but it just didn’t work for me. I felt like, if I’m trying to tell a story I should just tell a story.

And I love film, and I think that painting and static images hanging in a gallery are, for better or for worse, not as culturally relevant as film is. In the two years I’ve been at BioWare, I’ve never come in to work and heard anyone discussing a painting they saw at a gallery. But I do hear discussions almost every day about movies. And, occasionally, books. But mostly movies ~ and TV shows. Do you agree with me at all about this?

Brenner: Well, I think that people at BioWare might be a pretty distinct subcultural set … but, at the same time, you’re saying that film, that video, and even stuff on TV, is much more culturally relevant in how pervasive it is. And yes, I do agree. In fact, it’s currently less bothersome that it’s culturally relevant. Because, years ago ~ many years, even ~ there was only network television stuff, and that was mostly crap. And so the cultural relevance of it, you’d wonder, what the fuck is wrong with people that they embrace such shit? What are they, idiots? But these days you can’t say that it generally sucks anymore. Because, especially with cable and the Internet, there’s so much good stuff out there. So I don’t think the greater cultural relevance is a bad thing at all.

Myers: Right. And, for me, this is coming from somebody who’s very into visual arts. I mean, I go to art shows and museums on a regular basis. I plan vacations around places that have works of art that I can go see. And I had lunch with Michael Sieben the other day, and he’s somebody who’s made a splash in the visual arts scene, whose work I admire. And I was kind of surprised to hear him agree with me on a lot of these points.

I have a degree in studio art with a minor in art history, and I love talking about art and thinking about art. And it’s easier for me to justify a work that’s moving, that talks, that tells a story. It’s easier for me to feel, in creating something like that, that it justifies itself somehow. Whereas, when I finish a painting, I oftentimes wonder, “Why did I just do that? What is that?”

That’s just a personal hang-up, maybe. It’s a weird thing. I would love to have a better understanding of how to create static images and be satisfied with them. I’m a big fan of static images, I’m just not a big fan of my own static images.

Monday, April 9, 2012

RUSSELL ETCHEN:

The Man Behind Austin's Domy Books

(Or, in this case, yes: The man in front of it.)

PHOTO BY CASEY JAMES WILSON

MAYBE YOU SHOULDN'T BE WALKING INTO DOMY BOOKS.

If what you really want is sequential art featuring super-powered people dressed in various forms of Spandex and generally beating the super-powered shit out of one another, then you should go to Austin Books & Comics ~ because Austin Books & Comics is the best place in all of Texas, and one of the best in the whole country, to assuage your jones for the latest adventures of the Fantastic Four and Green Lantern and Iron Man and the Runaways and that whole crowd. And only because the store is so well managed, so thoughtfully designed to attract and welcome, as if in spite of the depths of its geekery, will you also find a sweet array of non-superhero and indie titles (alternative comics, right?) and thick volumes of collected illustration and so on, gladly pointed out to you by the helpful staff. It's a terrific place, Austin Books & Comics.

BUT.

If you're looking for just a few of those alternative comics, and you don't give a mutated rat's ass about Captain Steroid-Man Versus The Nefarious Nematode or whatever; and maybe you also want to have your eyes expanded and your mind blown by oversized volumes featuring the wildest street styles or the rarified conceptual stuff, by handstitched zines and skater rags and faux-brow periodicals, by the sort of slick graphic-design compilations and photographic anthologies that would give the collective body of the AIGA a raging hard-on; and, hell, you'd actually enjoy a display or two of Dunnies and Labbits and miniature Gundams; and, sure, you'd totally love a gallery of original art right there in the same store?

THEN YOU SHOULD BE WALKING INTO DOMY BOOKS.

That's where, as The Austin Chronicle put it when they awarded Domy the ‘Most Dangerous Store for Graphic Design Addicts’ award in their 2009 Best of Austin issue, "Russell Etchen is your towering ginger guide to much of what's best about having eyes and the knack for pattern recognition."

Well, yes: Etchen is the manager of the store, after all. He started it in Austin after he and some friends were successful with the first Domy Books in Houston. He started the store; he stocks it well; he hires good people; he schedules the readings and the presentations and the exhibitions in the big one-room gallery; he makes connections with artists and publishers around the world and brings his favorites and their wares into the impressive Eastside venue. And he is towering ~ well, he's 6' 4" ~ and he is gingery.

But, like, what's his story?

"I was brought up in a very Christian home,” says Etchen.

[He's sitting in Domy's back room where, months before, a life-size and disturbingly realistic model of the murder scene of Mary Kelly ~ Jack the Ripper's final victim ~ was on display, the body having been rendered in latex and placed upon painstakingly recreated furniture (with everything, even the desecrated flesh, in shades of gray: like the photo on which the scene was based) by the proprietor's friend, sculptor David N. Allen.]

"This was in the suburbs of Houston ~ in Clear Lake, near NASA," says Etchen. "Everything I was allowed to listen to also had to have roots in Christianity, except what my parents listened to ~ which was ‘50s pop music and ‘70s psychedelic records and things like that, from before they were Christian. Otherwise, I had no reference for culture ~ or current events, even. My parents and I, we had no common interests, except for talking about God. And, uh, I never really got down with that program.

"And then, around age 12, my dad got me a subscription to Mad magazine. Which was against everything he brought me up with. It was almost like my dad was secretly trying to subvert me ~ without my mom knowing or something? ~ even though he could only go so far. And from there I got into comicbooks, which were secular. But comicbooks were fine, and popular music was not. The Simpsons were not. There were a lot of very weird inconsistencies in what I was allowed to do or not do.

"Then, when I was 15, I met these kids from Chicago, twin brothers. We were in an office supply store with our moms, getting ready for the sophomore year of high school, and we both had on the same cartoon T-shirt ~ it was for a comicbook called Bone by Jeff Smith. So we were these 15-year-olds in the Office Depot, and I spotted the shirt that I was wearing, and without hesitation I went up to this kid and I was like, "You know about this?" Because this was in '93, I think, and Jeff Smith had just begun, was maybe six or eight issues into it? And me and the brothers became immediate friends.

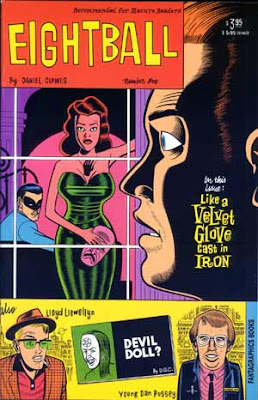

"So I had this, like, twin crew. They'd been brought up in the suburbs, too ~ very Catholic. But the difference is that their dad would take them into Chicago to go to Quimby's Queer Store, so they got exposed to many comics very early on. So, the first day I'm hanging out with them, they're showing me Dan Clowes's Eightball, they're showing me the original Xerox copies of Optic Nerve, they're showing me John Porcellino's King-Cat. And I was hooked. I dropped all superhero comics and got completely into alternative comics.

"And with these two guys, who ended up moving away about a year later, we managed to put out a whole bunch of stuff. We did an anthology comic called Velvet that was terrible. I made zines about dancing; they made zines about the stories they wanted to tell. And, for like a year and a half, we didn't have any friends outside of our crew. We'd just go and hang out all night at the Kinko's nearby and scam the shit out of them. We'd walk around ~ we weren't doing drugs, we weren't drinking beers, we weren't even smoking cigarettes ~ we were just straight nerds. None of us had girlfriends; none of us could talk to girls. We just sat around and listened to college radio and the Velvet Underground. And we made videos, these weird documentaries that we made about ourselves, just shot them in their room, making shit up, making stories up.

"And so I completely immersed myself into zine culture. Because I needed that. All my social skills, everything that I learned about being friends with people, came out of writing letters. Every day I'd come home from high school and I'd look at the mailbox and there'd be four or five zines waiting for me. And I'd send mine out in trade. There was a magazine about zines, called Factsheet Five. And Porcellino used to run a distro called Spit and a Half, selling minicomics and zines from his house. And at one point he was distributing our zine, and I discovered all sorts of people because of Spit and a Half. That's how I discovered Ron Rege, how I discovered a guy called Al Burian, who's been writing this book called Burn Collector for years. My whole world was opened up because of zines.

"And then I found punk rock and got really involved in music for a long time. Me and my friends ran a booking collective in Houston called Hands Up, and that lasted for four or five years ~ and we brought hundreds and hundreds of shows to Houston that weren't coming before. And then I got burned out on that and got a real job and finished school. I'd kind of fallen out of self-publishing for a few years, had no real desire to share what I was thinking about with anyone. And I decided that if I was ever gonna do that again, I'd only do it for my friends ~ because your friends are the only ones who care about it anyway, so you might as well just stick to what you know."

[At this point ~ and you may think that your reporter is pulling your leg; you may suspect this is some sort of orchestrated, Paul Auster-like coincidence of plot; but, no, it's true, this is exactly what happened ~ David Allen, the sculptor, walks into the back room with two cold bottles of Stella Artois: It's a surprise! Etchen introduces us, and there's much cheerful huzzah and hands being shaken and fists being bumped all around. Allen takes a nearby chair, Etchen and he crack open their crispy Stellas, and the three of us get to talking about the Mary Kelly piece and about Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell's From Hell and about the genius of Alan Moore in general, and about plans for future projects. And then Allen leaves, and it's just me and Etchen again, and it's time to ask about Domy itself.]

"I worked a regular job in Houston for three years," says Etchen. "And then, my girlfriend at the time was working for Magda Sayeg, who's the wife of Dan Fergus, who owns Domy. Magda had a store called Raye, and I was hanging out there a lot ~ and at Brasil, the cafe that Dan also owns. And one day Dan was like, 'Look, how can I get you to work here? I have this extra space, and I don't really know what I want to do with it. I know how the food industry works, but I don't know retail.' And I said, 'I don't know how business works, but I know what I'd stock.'

"I could see the whole store in my head. And I knew all the places to go to get the stuff, because I'd been sitting on the information since I was 15 ~ the things I was accumulating, the knowledge I was gathering, I was like a sponge. And I couldn't really share it with anybody, either ~ because, out of context, it's just a bunch of nerdy stuff that very few people care about. But when you can actually put it in their hands and talk to them about it, it totally changes everything.

"I think about those first few moments in your adolescence, when that first thing clicks, the first time somebody does something, introduces you to something ~ whether it's a record store employee or you see something in the back of Spin magazine. Whatever that moment is, where, suddenly, your world opens up a little bit and you're just blown away. Like, 'Oh my God, I didn't know this was out there!' Those moments are so sacred to me, and I wanted to replicate that experience for other people. I wanted to get kids into the store, but also have a place that was gonna appeal to a hardened, jaded consumer or art collector, a person who's seen it all and done it all and is kind of looking for other things.

"So, along with Patrick Phipps, who also runs the Menil bookstore, and my friend Seth and the owner, Dan, the four of us opened the Houston store in four months. And we just celebrated the four-year anniversary on April Fools' Day. And this year, this shop is coming up on two years in June ~ June seventh. And we're doing great. We're not raking it in, some months are better than others ~ but we're paying all our bills, we get a lot of great artists in here, and a community is really developing around the place."

[Congratulations are offered there in the back room, where the ghost of the latex model of the last woman who was killed by a surgically skilled maniac in London in 1888 might still haunt anyone who saw last year’s grisly circa-Halloween installation. And Russell Etchen, the tall ginger proprietor in jeans and an untucked button-down, grins ~ because the store's success is no small matter to him. Because, to him, the store is … what?]

"Domy Books is a place where I can share all the things that I'm obsessed with," says Etchen. "Even if I'm no longer interested in some of them. I had my moment with them, and it's done, and I can talk about it. There are some things that I'm interested in that I don’t share here, because I'm still exploring them for myself. But, yeah, it all pretty much goes back to Mad magazine for me. Cartooning, comicbooks, and punk rock. I will forever call myself a punk; I will forever claim that ~ because that's how I feel. Because being a punk isn’t about fucking shit up; it's about, you know, being open and willing to try things out that you wouldn't normally try."

Saturday, April 7, 2012

JACQUELINE MAY

isn't blind to the beauty of braille.

She isn’t blind at all, in fact: The artist sees quite well, thank you ~ even better without glasses than some of us do with glasses. Her deep blue eyes have successfully watched her dominant hand guide a paintbrush for many years, have observed and abetted the creation of works ~ in acrylics, in encaustic wax, via lithography, with gold leaf and aluminum leaf and more ~ that have improved the walls of Gallery Lombardi, Arthouse, Women & Their Work, Studio2Gallery, and San Antonio’s Galeria Ortiz. It’s just that, especially in recent years, Jacqueline May has used braille to enhance, to complicate, to inform those works.

THE WORD MADE FLESH

“I’ve always been interested in secret-code type things,” says May, over java and a piece of rich sweet cake at Quack’s 43rd Street Bakery. “But what got me interested in braille, specifically, is that I was doing volunteer work at the Recording for the Blind center on 45th Street, and I was seeing all these braille things in my immediate surroundings. And it sort of clicked over, like this is another thing, this is another secret code that some people can read and other people can’t, like another level of meaning that’s embedded in our everyday reality. A stealth thing. Like those ancient photographs that have been exposed by some arcane process, that tell us a secret or something about our environment that we wouldn’t otherwise know.”

Brenner: What was the first piece that you used braille in?

May: It’s been a while, but I think I started out by using cut-out dots on some drawings. Then I got intrigued by these sheets of clear dots that I had, that are for sticking on the backs of paintings. I had sheets and sheets of them, so my paintings wouldn’t scuff up the walls. And the little dots had their own existence ~ they were pretty little things, all rainbowy in the light, looked like drops of water. And I started sticking them on my studio wall … and, uh, a movement was born.

Brenner: A movement that involves braille and … fish?

CHARON'S FLOCK

May: I shot this video in Chinatown, in San Francisco, when I was traveling. I was going through a lot of internal stuff about reuniting with my birth family, and some of that came out in the video as looking around at my surroundings. There were these fish, swimming around in a tank at a fish-seller’s stall, swimming back and forth. And it just struck me how they were fated to die. Like seeing the human condition, how we’re all here, swimming around, waiting for our ultimate demise. And here’s this fish-seller on the other side of the tank, and you order from him ~ “That fish right there!” ~ and he takes your fish and dispatches it for you.

So I shot this video, and as I’m shooting this fish tank that separates you from the fish-seller, I pan around, and there’s this long row of skyscrapers on either side. And you get the sensation that you, yourself, are in a fish tank.

Well, I don’t know if too many people got that out of the video, but it was my private story that I was making for myself. And that’s where the painting Charon’s Flock came from. And because I’d started doing the braille work at the time, it seemed like a natural progression to drill holes in the painting and install lights behind the holes. And the holes are the braille version of a quote from Walt Whitman:

Whoever walks a furlong

without sympathy walks to

his own funeral drest in his shroud.

So there’s this poetry that occurs because there’s light coming from the holes, but, for someone who’s blind, they’re never going to see that light. And it’s like a marriage of complex flavors, like when you sip something that has a really complex taste: It’s a visual parallel to that. And I’ve used braille in lots and lots of other things since then, it’s become a standard.

THE FLOW

Brenner: Have you had feedback from people who are blind, who’ve experienced any of the braille that you’ve used?

May: Yes ~ and they really enjoy that somebody has thought about them in creating artwork. But I can’t say, to tell you the truth, that the foremost thing in my mind was “Let’s go and make artwork that’s accessible.” That was secondary to the initial concept.

But, at the same time, as a person who has a heart, I do care about people having access. And it also opened the door for me, to some opportunities that I wouldn’t otherwise have had. In July, I’m going to be in Norway, in Christiansund, doing a braille installation there. It’ll be in between the health center and the public library, there’ll be rainbowy dots on the wall … and I’ve been talking to a couple of friends about the possibility of throwing in some runes for craziness’s sake.

Brenner: Jacqueline, have you made any art recently that doesn’t incorporate braille?

May: Well, I’ve been doing some video artwork lately ~ although I’m throwing some braille in that, too, as a sort of frustration factor. It’s just a funny, quirky thing. People see these dots scrolling across the screen and they think, “Oh, a pret-ty lit-tle pat-tern,” and it’s just an inside joke for me and my two best friends. Of course, now I include you into that circle.

Friday, April 6, 2012

STEVE BRUDNIAK:

Whatever you do …

PHOTO BY DAVID JEWELL

Really, steampunk is the wrong word.

Because the steampunk impulse springs from a desire to embody a fictional existence within the context of our putatively duller reality, to engage in a sort of retro-cultural cosplay ~ regardless that it's a form of cosplay both less specifically derivative than most genre-based costuming and more often on par with inspired pinnacles of mainstream craftwork.

And that's not what Steve Brudniak is doing.

Right?

"I don't know," says the artist over coffee at the Green Muse Cafe on Oltorf Avenue,

"I wonder if ~"

No, steampunk is the wrong word. Because what Brudniak is doing is another thing entirely. He's not forcibly regressing modern tech toward some brass-hinged Victorian aesthetic for the delight of those who might yearn for a brighter, more mechanized version of (mostly European) days gone by.

Right?

"I don't know," says the artist over coffee at the Green Muse Cafe on Oltorf Avenue,

"I wonder if my denial of steampunk ~"

No, nevermind the steampunk. What Brudniak is doing in his Bouldin Creek studio that's equipped with drill presses and table saws and arc welders and industrial-strength angle grinders … what he’s doing in that workspace where the walls' shelves are chockablock with thick lengths of molded aluminum and iron, with copper tubing and johnson rods, with lenses and lasers and antique tiles and porcelain fixtures and dismantled apparatus that looks ripped from the guts of a Decepticon … what he has been doing there for almost three decades is using salvaged scientific and industrial equipment to create eerie structures that embody a timeless, ur-technological style. He's constructing machinelike (and painstakingly machined) objects that often serve as thick-plated frames or repositories for more fluid and personal … things.

It's a completely different motivation.

Right?

"I don't know," says the artist over coffee at the Green Muse Cafe on Oltorf Avenue,

where several of his scientific-looking sculptures are installed. "I wonder if my denial of steampunk might, ah, come back and bite me in the ass someday."

THE VAGUS LEVIATHAN

"I started out working with found objects in about 1982," says the artist, tearing hungrily into a thick Green Muse sandwich. "Which makes it, what? Longer than time is supposed to be. Twenty- eight years. And I just fell right into it, too. I started with some clay and went right to a neon-sign transformer after that. I was … 22?

“I was a bit of a science nerd, starting out. I think I just found the transformer at a neon-sign dump, and it said, on the side of it, that it would put out 15,000 volts. And what comes out of the wall is 110 volts. So I thought, hey, I'm gonna see what this does, and started playing around with it. Because you can take the two electrodes and you get a two-inch spark going like bzzzzt! between them."

"Like a Jacob's Ladder?" says your reporter.

"I actually made a Jacob's Ladder with coat hangers," says Brudniak. "And I had a landlord who worked for the electric company, and he said, 'Oh, transformers like that, you can't even get near them, a spark could just jump out and kill you.' And I didn't realize that he was talking about the big transformers up on the lightpoles. So for the first month of me playing with this neon-sign thing, I'd get a broomstick and poke it with that. And I started experimenting with fruit, cutting a banana in two and sticking the halves on the ends of coat-hanger wire. And electric sparks started jumping between the two halves of the banana ~ because, y'know, there's moisture in a banana, so the water conducts the current. And I ended up making my first sculpture, which was a carved wooden banana and a little angel from a Dungeons & Dragons set, a metal angel that's holding a staff, and the banana comes down, and there's ~ bzzzzzt! ~ a little spark that jumps to it. And it's all in this glass case, gilded, in stained glass. You can see it on my website."

"From the start," says your reporter, munching a few Zapp's salt & vinegar-flavored potato chips that the artist has kindly offered him, "you've set your works up as parts of an exhibition from some giant, gorgeous museum that doesn't actually exist. With the glass cases and the gilding, as you say, with the frames and all. What made you decide to do that, as opposed to just 'Okay, I've finished this object, now I'll move on to the next one?'"

"I've always had a real fascination for science museums," says Brudniak. "Since I was a kid, I've loved the displays in science museums ~ and art museums. Just the fact that something has been made precious by being surrounded by glass, in a vitrine, or framed and on the wall. Like, have you seen the photograph, the World's First Photograph, at the Harry Ransom Center? It's got a booth of its own; and then you go into the booth and there's a glass case; and in the case there's another case full of nitrogen; and in the nitrogen case is the photograph ~ inside a picture frame. And there's something gorgeous about that.

"So, yeah, almost everything I do has a central, ah, focus. Like a window or a tube or a case. Something that's being held, behind glass. And some of that relates well to the human, ah, psyche, you know? How there's this whole body that we've got that ages ~ it gets older and starts falling apart, gets gray … but inside there's still that little seven-year-old kid, you know what I mean?"

"Sure ~ it's preserved," suggests your reporter. "Like with the reliquaries you make, right? With your mentors' blood in them … ?"

"The blood reliquaries, yeah," says the artist.

"They're over at the East Side Show Room right now."

"And what got you started on that, on putting human fluids in with all this mechanical stuff?"

BLOOD OF A MENTOR: CULTIVATOR OPTIMISM AND HUMOR

"Well," says Brudniak, "I'd been using biological things previous to that, too. And I'd seen a Catholic relic called The Blood of St. Genarius. It's this pole that the Pope or a bishop or somebody holds. It's all fancy, and it's got this glass bowl or jar at the top of it. It's this giant wand that the bishop uses. And what's in it is the blood of St. Genarius, and it's coagulated. But the bishop does a ritual, and starts to move the pole, and the blood magically becomes fluid ~ supposedly. And I saw that, and I thought, wow, what an awesome idea. Because, what is it? It's a relic. It's a relic that's been framed and put into a context where it's on display ~ and so it's a reliquary. And the Buddhists have their reliquaries, too, like the bones of their saints. So I thought I'd just use my own saints ~ or people who had affected my life."

Brenner: Which people in particular?

Brudniak: I went all the way back to my best friend in fifth grade, who was like the guy who pulled me out of my early nerd-dom. He'd be like, "Steve, let's jump between these two buildings!" And we would. And another friend who, later on in life, was one of my spiritual guides and teachers, in a way, who taught me a lot about Letting Go. And my parents are in one reliquary. And a good friend of mine who taught me a lot about how to laugh and be optimistic. And another one is an ex-girlfriend who taught me about benevolence and giving. There could've been a lot more reliquaries, but those pieces take a long, long time to make.

BODHISATTVA SETTEE

Brenner: Do you draw the blood yourself, or do you have a dedicated phlebotomist

that you work with?

Brudniak: I have two doctors who help me. And, oddly enough, my friend from fifth grade had always wanted to be a pilot, and I hadn’t talked to him in twenty years, and when I finally got in touch with him through the interwebs, he was like, “Hey, I’m actually a pilot now.” And I told him about the reliquary project, and I was like, “Can you do this?” And he goes, “Well, you know, I happen to be flying to Texas tomorrow.” And I go, “Oh, really? Where you going?” And he goes, “San Antonio.” And I’m like, “Guess where my doctor lives.” And so, the next day, my doctor’s drawing his blood.

And I have a psychiatrist friend who’s also collected some of my work; he did my parents. My dad’s like, “Steve, why the hell do you wanna use my ~ why couldn’t you put flowers or something in there, something that’ll sell?” It was tough, getting my parents to give it up, but they did it.

And then my friend, my guru buddy ~ who’s actually dead now ~ I had to go to Oklahoma to get his blood. But I couldn’t find a doctor in Oklahoma, so I went to a hospital and went to the supply room, and talked the guy there into giving me the phlebotomy kit. I’d seen it done enough times ~ I’d been a guinea pig at Pharmaco, so I’d had my blood drawn, like, eight million times when I was in my late twenties. So I did my first and only blood draw, ever. Luckily, this friend of mine had huge veins. And I did it perfectly: he didn’t even flinch! So I got his blood, and that was fun. Fun and scary ~ because I’m real squeamish about blood, so it helped me get through that.

There was one point, where I was filling up one of the reliquaries ~ and you have to get a syringe and squirt the blood in, and you have to have an outlet for the air ~ and I filled it up too far and some of the blood just ~ psssshhhhh! ~ it sprayed out onto the wall. And I remember getting really dizzy. I almost passed out working on my own art.

Brenner: What about that arrangement with game designer Richard Garriott, where you got some reliquaries taken to the International Space Station? How’d that come about?

Brudniak: I met Richard a long time ago ~ back in the Eighties. And he had a Tesla coil, and I had made a piece of art with a Tesla coil ~ the San Antonio Museum of Art owns it now ~ and I’d kind of met him back when we had a science museum here: Discovery Hall. I didn’t get to know him very well … but there’s a group of artists called The Robot Group, real sweet group of people who are doing some neat stuff and bringing technology to kids, and another group called Jumpstart, and we got city grant money to do science workshops with kids at schools. And I think it was through one of the guys in The Robot Group that I got Richard’s number. And I sent him some photos of my work, and he eventually got back to me and said he wanted to buy a bunch of it. And he did; he bought a few pieces from me.

And a few years later, he came over and bought some more work. So we began kind of a dialogue, and once in a while we'd chat online, and I got a tour of his awesome house. And then I heard him on the radio, talking about going to the space station. So I emailed him and said, "You know, I have this idea. If I make a piece of art, and you take it to the space station and bring it back, I'll let you keep it." And he was like, "Well, that's a great idea, I'm gonna be bringing up some of my mother's watercolors … "

But he told me that the artwork had to be very small and not be able to crack or break and so on. And I'd been thinking about doing little blood reliquaries, but Richard said it couldn't be anything that could potentially contaminate the air in the space shuttle. And his father was an astronaut, so I got a clipping of Richard's hair, and a clipping of his father's hair, and got these little Cartier watches from the Seventies ~ these were fake Cartier watches ~ but they have a cool little window, kind of square, and there's tiny screws all the way around. I happened to find two of those at a thrift store and I'd been wanting to do something with them. So I pretty much ground everything off the watch until there was this perfect little window, and I took the guts out, put a little velvet in there, and stuck some of their hair in each one.

My plan was that I would keep one, and Richard would keep one. And he didn't really do an art show up there, but I have a video where you can see him doing a demonstration with some tennis balls on the space shuttle, and the watches are stuck on this bulletin board behind him. He put Velcro on the back of them ~ everything he had was literally stuck on this bulletin board. And I was watching the video, and I was like, "There they are! There they are!" But Richard's plan was to keep both of them. Which he has, so far. But, fortunately, I have two other pieces of art that I borrowed back from him …

HEIROPHANTIC APERTURE (SAMSARA)

Brenner: So by now you're making a living from your art?

Brudniak: It's always now.

Brenner: You … uh, you've always made … a living from … ?

Brudniak: No ~ it's always now, Brenner.

It's always now. This is the moment.

[Nota bene: The wry grin, the Zen sparkle in the artist's eyes. Nota bene: The frown, the flow-thwarted frustration in your reporter's eyes. Nota bene: He's a sincere man, this Brudniak, a decent man; but he will fuck with you.]

Brenner: No, I mean ~ look, at some point ~ at some point ~ including now ~

you started making a living by selling your art. Is that right?

Brudniak: I've always made part of my living selling art, because, eventually, I sell every piece that I make. But some of them take a while ~ like that very first piece, with the wooden banana: It was a very good piece, but it took twenty-some-odd years to sell. And I'm just now getting prices on my work where I can ~ I mean, if I sold everything I made, immediately, I couldn't quite make a living at it. Because, in a good year, I can only make two or three large pieces a year, with another five or so smaller pieces. In my best year, I think I made nine pieces of art. The piece I'm working on now, I've been working on it since last October, maybe earlier than that. And hopefully somebody will buy it and I'll get close to $20,000 or so for it. But it's a tough sell ~ somebody's got to want a weird-ass thing, and they have to have room for it. They've got to be rich, pretty much. I certainly could never afford …

Brenner: To buy your own art?

Brudniak: Yeah, you know? The really sad thing in the art world is that, if you go 25 or 30 years and you're still selling your big pieces of art for a thousand dollars, people are gonna be like … well, the collectors want to buy valuable work that's valuable, you know? So I raised my prices a couple years ago and was still able to sell stuff. But it's a slow process. I rent out space, part of the property I own, and last year was a really good art year ~ so my income was split about fifty-fifty, between the art sales and the being-an-evil-landlord sales. But the only reason I bought the property and turned it into rentals was so I'd have time to make art and not have to worry about whether I sold anything. Because the market is so unpredictable.

Brenner: And times are hard.

Brudniak: And people have different tastes ~ everybody buys for different reasons. You might buy a, like, a Jeff Koons because you can invest with it later or something, you know? There's a lot of people that are infected by the Emperor's New Clothes virus: Ninety percent of the art world is.

Thursday, April 5, 2012

NAKATOMI INC:

The Amazing Adventures of Tim Doyle

in the World of Limited-Edition Prints

PHOTO BY JON BOLDEN

He’s not a robot, no.

He’s not made from the same material

as those giant Transformers he enjoys so much.

But Tim Doyle, ladies and gentlemen, Tim Doyle is a fucking machine.

That’s why the man was able to run three different comic-book stores at once. That’s how he could take the Alamo Drafthouse Cinema’s Mondo Tees store and guide it to become the successful, internationally acclaimed graphic-design venture it is today. And that’s why, post-Alamo, he’s achieving the same thing with his own Nakatomi Inc. while helping his wife raise their son and infant daughter and ride herd on what seems to be a constant flood of stray and/or adopted cats.

Because the short, hefty, raven-haired and quick-witted artist, curmudgeon, and serial entrepreneur is a machine.

“Brenner,” says Doyle, shaking his head, scooting another cat off his busy drawing table. “I’m not a machine. Dude. I’m just as human as you are.”

“Tim,” I tell him. “Metaphorically, Tim.”

“Brenner,” begins Doyle, but … is distracted as two more cats, appearing as if from some eldritch portal, grab hold of a still-wet paintbrush.

Of course it’s not just the drive of this man that equals success. No, Timothy Paul Doyle had a lot of raw talent to begin with, yes, he could do certain things with marks on paper, things that resembled the real world at least enough to be recognizable. But that foundation only led to more effort; even that advantage was met with further diligence. Doyle honed his talent over time, producing numerous acrylic paintings of, e.g., Vespa scooters and oldschool telephones and personal friends and pop-culture icons … writing and drawing a daily journal in three-panel comic form, covering every waking day for two years … creating those first movie-based posters when he started at Mondo Tees.

And then came The Interglactic Nemesis.

Jason Neulander’s old-timey sci-fi radio serial, performed live by a sharp cast of voice talents (and featuring Buzz Moran on sound effects), was a cornball throwback to the ripping yarns of yesteryear. It was also, Neulander figured while plotting to spread the goofy hit across as many media as possible, perfect for adapting as a comicbook series ~ with the comic-book further adapted as a quasi-animated slideshow, to be projected on a giant screen behind the internationally touring cast.

The adaptations would require hundreds of new, full-color images, dozens of pages of sequential art hewing to the mutated script, and all of it on a tight schedule with deadlines harder than, oh, I don’t know, adamantium?

Doyle was offered the job; he took it and charged right in.

Accommodating that much illustration under those conditions, turning out seven complete issues of around 28 pages each (in addition to collateral graphics) in one year ~ all while making sure Nakatomi remained a viable business ~ was the creative boot camp that pushed Doyle’s drawing and page-composition abilities from yeah, that’s pretty good all the way to Okay: Doyle, Pope, Cooke, Los Bros, ah, I suppose it’s just a matter of what sort of thing one is looking for at the time, y’know?

Seriously: Just look at the pieces included here;

or at the greater variety on that Nakatomi site.

Impressive? Certainly. And yet another reason

for me to shut up and let the man himself do more of the talking …

Vietnam on Wheels

Brenner: So, above this sentence, that's what I first saw in the Bicycle Prints show at Gallery Black Lagoon: the Vietnam on Wheels poster that seems a bit more, ah, subdued? More subdued than the work you usually do. Tim, what can you tell me about that one?

Doyle: I was really happy with the way it turned out ~ it looks different from anything else I’ve done. And I picked the 16 x 20 size, too, because it’s a size I haven’t worked in before, and it forced me to make a couple of different compositional choices. It’s not out of my wheelhouse as far as the drawing method, but the subject matter is.

I’d just finished a poster for Apocalypse Now, and a couple months before that I’d done a poster for Full Metal Jacket. And I really like the way Vietnam looks, so I was doing a little Googling around, and there’s this Flickr group called Vietnam On Wheels, and I was overwhelmed by all the scooters and bicycles and the different forms of transportation, the three-wheeled motorcarts. And there was an artist out of China, actually, who did this amazing print of Chinese street life, and I was like, “Oh boy, I really want to do that.”

Because I do a lot of cityscape stuff. Like that Reservoir Dogs print, there’s Harvey Keitel and the car and the blood, and it really looks cool, but I’m really into drawing the trainyard and the telephone pole in the background. I just really like city junk.

And Asian countries ~ Vietnam in particular ~ it looks like it’s still on planet Earth, yeah, but it’s just weird enough, y’know what I mean? None of the signs are in English, obviously, but they’re still using the English alphabet, which I guess is from the French influence. But what really gets me is the way their electrical grid is put together, like everything is bolted on and thrown onto these buildings? Like, in America, there’s powerlines everywhere, but we go out of our way to make them not so obtrusive? But looking at the Vietnam streets, it’s like, now that is an electrical accident waiting to happen. And it’s really appealing to me.

Brenner: How has doing comics, sequential art, influenced your compositions

for a single-panel work?

Doyle: A lot of the stuff I do, I kind of try to capture a scene in a story. And when you’re doing comic-books, you have to leave a lot of room for the lettering? Which means you have to make compositional choices about all the breathing space in the background. Like, it can’t just be close-ups of faces, or else the lettering bubbles are gonna wind up on everybody’s forehead. And I think that influenced me a lot, working on Intergalactic Nemesis and having to put in a lot of, I mean, it’s a wordy play, in many regards, so you have to leave a lot of space for word balloons. And when you get away from that sort of thing, you’re like, “Oh, wow, what do I do with all this extra space back here?” And you start drawing the trees and the surrounding environment. And I’m obviously influenced by Geof Darrow ~ I love his stuff so much. And no matter how much detail I put into a panel, there’d be still another detail that Geof Darrow would have put in. His stuff is like a fractal: The closer you get, the more there is to see. A lot of poster artists take the easy way out and just do big portraits, you know, a big essential image. But I’m more interested in setting an environment.

The Sea Also Rises: King Crab

Doyle: It’s graphic design versus illustration, is what it comes down to. I like to think my posters are well graphically designed but still drawn. Something I’ve learned by looking at a lot of comic-book art is that most comic-book artists are not good graphic designers. They can tell a story through art, which is important, but they can’t … like, there can be a guy who does amazing interiors but he can’t draw a cover to save his damn life. Because the cover has to hang together in the way a single panel doesn’t. That’s something I’m learning more and more as I go on.

Brenner: So you’re running a successful business; you’re creating your own works and selling them; you’re commissioning works by other artists and selling those; you’re making original illustrations for some pretty high-profile galleries and venues; you’re making a living doing what you love. Why don’t all artists do this sort of thing?

Doyle: People get this tunnel vision, y’know? Like “I wanna get my artwork out there, and it’s gotta be this specific way,” and they miss all these other opportunities. In the modern marketplace for art and music, the old ways are dying off, and you’ve gotta get with it or else you’re in trouble.

And the pop-culture silkscreen art game, it’s like I helped build that niche through my work over at Mondo. We built this whole collectors’ community. There was a community that was already into buying rock posters, and we took those same artists and had them doing movie posters, and the appeal was so much wider. Because people were like, “Oh, that’s a brilliant poster – but it’s for Phish.” Whereas everybody likes John Carpenter’s The Thing, so if you can get Tyler Stout, who’s a really good artist, to do his take on The Thing, that’s a home run.

I mean, I’m not saying that I invented pop-culture silkscreens, by any means, but we kicked it up in a way that I don’t think had been done before. And I decided I no longer wanted to be on the administration side of it, I wanted to be on the creation side of it. And here I am now: It’s what I do.

Apocalypse Now

I’ve got two people working for me. Sean Robb, who used to work for me at Mondo Tees, and Zane Thomas ~ who also used to work at the Alamo. They work part-time, maybe 25, 30 hours a week. Sean, because he’s got a license, does a lot of the errands for me. I can just loan him my truck and say, “Okay, I need this, this, this, and this done today,” and he does that. And when he’s not doing that, he’s printing. And Zane does all the file prep. Like, I do my own color separations when I’m creating a piece, but we do take on print jobs from other artists, so they send the files to Zane and he does all the prep and the printing as well. And Angie [Doyle’s wife] does all the accounting, the customer service, oversees the packing and shipping. And I talk to the artists, make the deals, and do my own artwork.

Brenner: And what time do you start drawing?

Doyle: It varies wildly, depending on what needs to get done. Like, the day before a big release, the day usually starts off with making the blog posts, taking photos, stuff like that. I’ll start drawing anywhere from 7 or 8pm to midnight, sometimes work until 2 in the morning.

I wish I had more time to draw, but there are just so many other details. And I really try hard to promote the other artists on the site, because, y’know, they’re coming to me and I feel I owe it to them to sell the artwork so I can pay them. Which is why I like to work with people who are ~ not that they’re hungry, like they’re poor or they need the money ~ but that they want to make it work. Because there are artists who reach a certain station, where they don’t have to hustle so much? And a lot of artists are pretty terrible at self-promotion. And if they’re not pushing it on their end, sometimes it doesn’t do well.

Brenner: And when it does do well, are you and the other artists ~ how to put this other than crassly? ~ are you raking in the dough?

Doyle: Well, here I am, two and a half years after leaving Mondo Tees, and I’ve quadrupled my income over what I was making there.

And all my deals with artists are 50-50. If it’s something I’m publishing of theirs, it’s 50-50. And I take all the financial risk up front. So if they do something really good, it works out great for them.

But it’s a crap shoot ~ you never know. Like, some of the best stuff I’ve ever done sells terribly. And some of the more mediocre stuff I’ve done sells amazingly well, so I know my barometer is off.

Brenner: But sometimes it’s right on, too, or else you wouldn’t be where you are right now. Which seems like a good place to be.

Doyle: Yeah, well, it’s not that I want to be famous or anything. But it is good seeing people say nice things about me on the Internet, y’know?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)